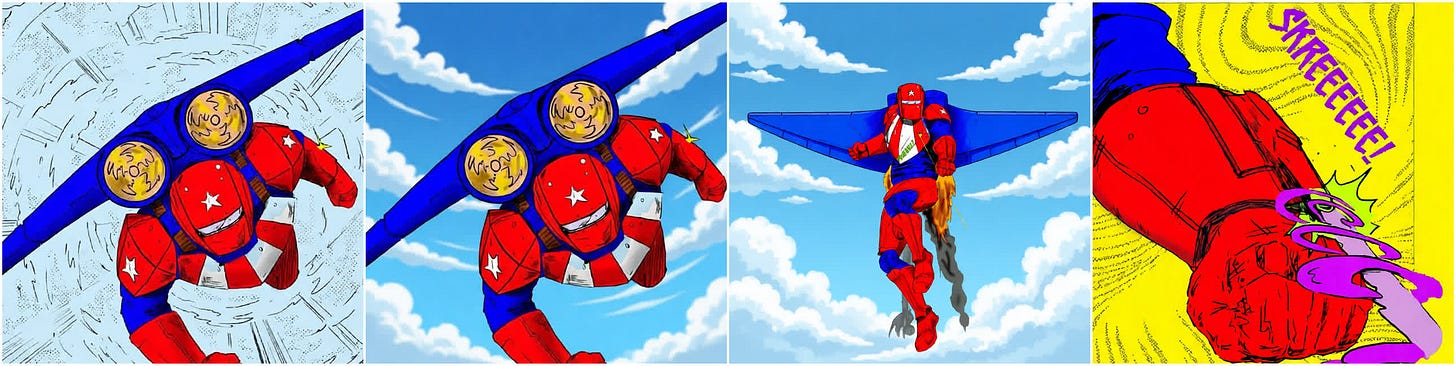

The other week, Henry Brown, author of Threat Quotient, posted regarding his troubles trying to make a quick video for his comic using online video generators. I suggested it might work better to use first-frame-last-frame models, got his permission to give it a try using images from his comic, and had at it. Above is the result.

Why

I’ve been meaning to play around with first-frame-last-frame video generation for a while, ever since Wan2.1 started supporting this last year, and Mr. Brown’s troubles provided the perfect excuse. Many human-made cartoons are made by providing intermediate frames linking the panels of an existing comic, and the ability to do this with neural network models opens exciting possibilities—comic authors making their own cartoons without needing a studio, and makers of illustrated fiction—like me—able to link their illustrations together to full-length video. The scene we wanted to animate had three sequential panels in the comic, making the perfect test case for these ideas.

Getting the models

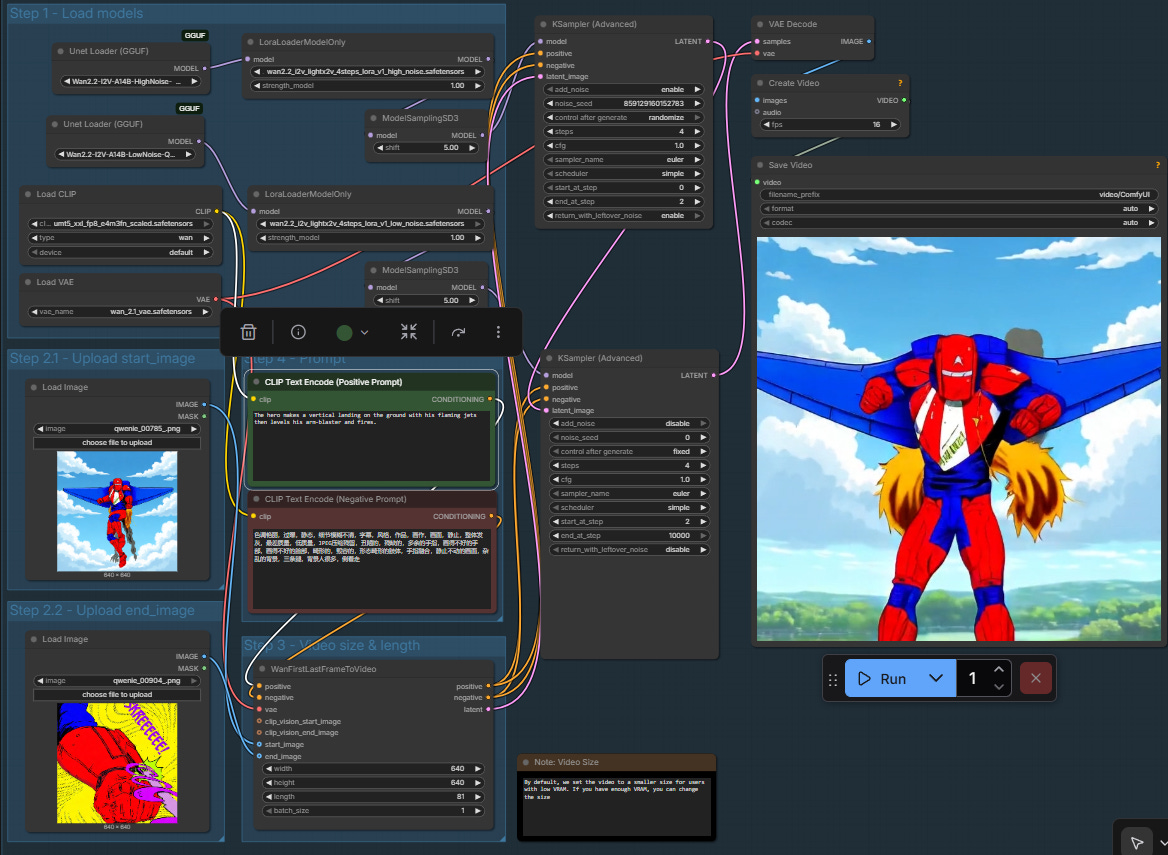

The current released version of WAN is 2.2. I downloaded the first-frame-last-frame workflow from ComfyUI’s official page here: https://comfyui-wiki.com/en/tutorial/advanced/video/wan2.2/wan2-2#4-wan22-14b-flf2v-first-last-frame-video-generation-workflow . I then downloaded the required models, except that I didn’t download the unquantized versions: instead I downloaded the Q6_K quantized ones from here: https://huggingface.co/QuantStack/Wan2.2-I2V-A14B-GGUF/tree/main . This reduces model size by more than 60%, giving something that would run reasonably fast on the 16 GB of VRAM on my laptop 4090. I replaced the model loaders in the workflow with GGUF (a quantization method) loaders, and I was off the the races. Workflow:

https://brianheming.com/pastes/wan2_2_flv_14b-q6-lightning.json

Testing it out

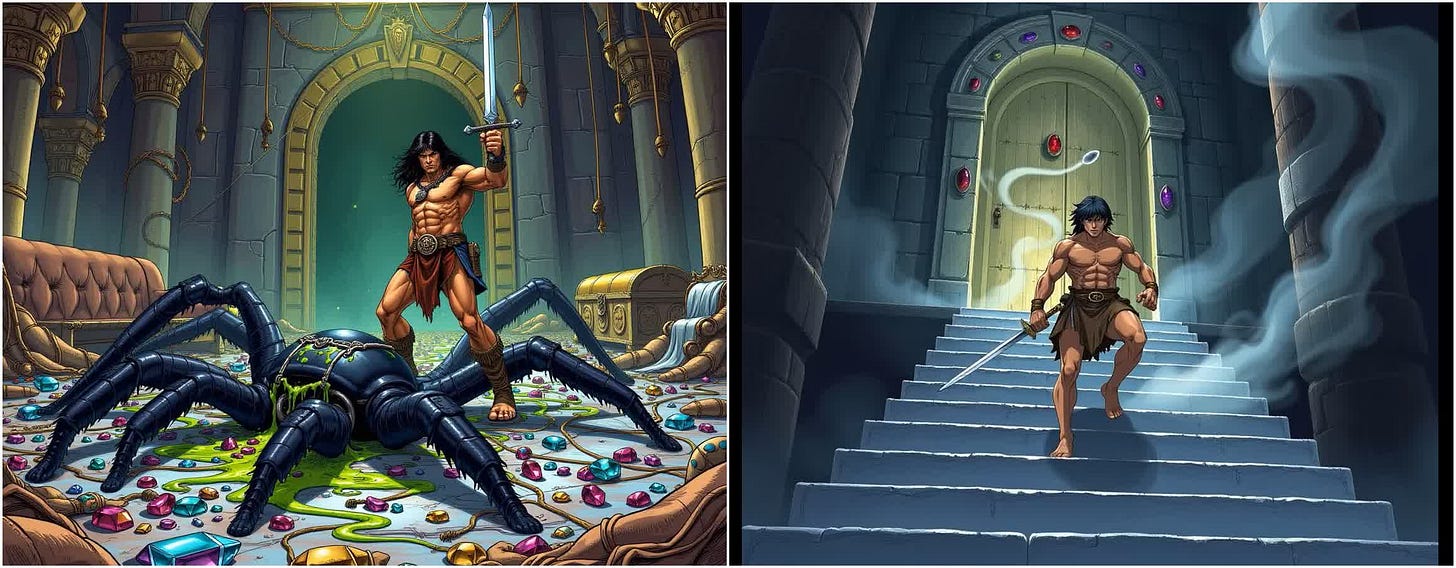

I made a quick test of the pipeline with a couple images from The Tower of the Elephant, an illustrated Conan story I just published. I tried both the 20 step workflow, and the 4-step lightning LORA which runs 5 times as fast. Results, with 4-step LORA on the right:

I can’t honestly say the 20-step one is much better, and in my experience being able to rapidly iterate and pick between a substantial number of versions vastly outweighs slight quality increases from high steps—especially as one can just take one’s favorite pick of results and further refine it—so I decided to go with 4-step lightning, which took about 3 minutes to generate.

The 4-step video also catches an interesting point I hadn’t noticed when I made the book: Conan is holding his sword in his left hand in the first image, and right hand in the second image, and the model has to bridge these by having him swap his sword hand. If this wasn’t just a test I’d fix it by mirroring the first image.

Cleaning up the base images

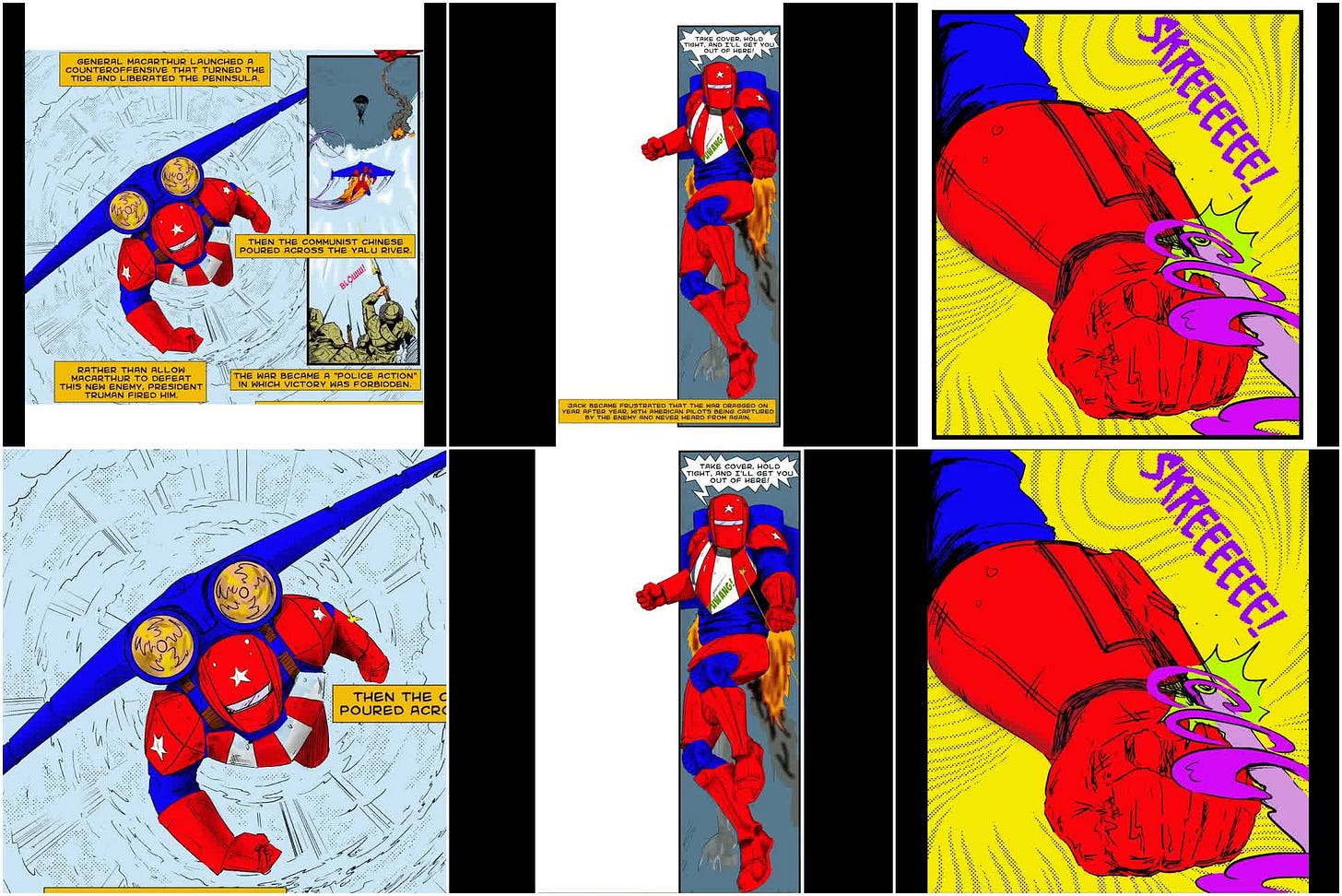

The scene we wanted to animate consisted of three panels from a comic, but there was a big problem: they all had different aspect ratios. Here’s the base 3:

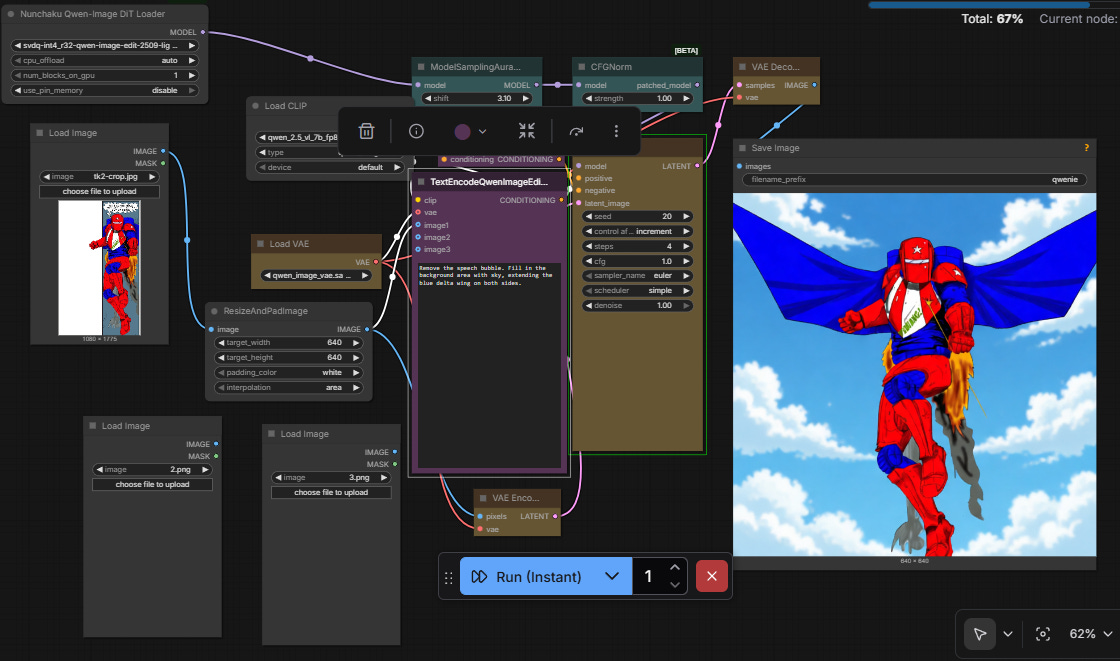

One is portrait, one is tall and skinny, one is basically square. I’d decided to just animate to my workflow’s 640x640 square default, so I took these and edited them to be square using Qwen Image Edit 2509 (4-step int4 quant). Here’s the workflow:

https://brianheming.com/pastes/QwenEditPad640.json

The workflow resizes and pads the image to a 640x640, then applies prompt-based editing. I initially just prompted these to delete text bubbles and fill in the whited areas, adding sky and extended wings in the background of image 2. Interestingly, “blue wings” typically always got bird wings, and “plane wings” didn’t work very well. I got better results by calling it a “delta wing”.

Animating the image1→image2 didn’t work very well with this, however—the model thinks the comic speed-line background is real and tries to make it work by animating the hero flying away from a painted background on the ground. So I went back to my editing workflow, had it change the background of image1 to sky, picked a result with sky and clouds reasonably similar to image2, and I was off to the races.

Another interesting thing is that the model doesn’t realize that the jets are fire unless you tell it—it will tend to just model these as decorative bits of paper. So I changed the prompt to include “flaming jets” instead of “jets”, and it worked much better.

Picking and Splicing

I generated 40 videos—23 of image1→image2 and 17 of image 2→image3—watched them all, and picked the best two. Here’s a montage of all of them for those who like seeing raw data.

Left prompt: The hero flies forward then goes up to vertical and begins a vertical landing using his flaming jets.

Right prompt: The hero makes a vertical landing on the ground with his flaming jets then levels his arm-blaster and fires. (the final 6 are repeats; the 6 takes I liked best)

Then I combined them with a simple ffmpeg command, and… done!

$ cat videofiles.txt

file 'ComfyUI_00022_good.mp4'

file 'ComfyUI_00042_good.mp4'

$ ffmpeg -f concat -i videofiles.txt -c copy tq.mp4Thoughts on Video Creation

On seeing the video, Centaur Write Satyr asked me how it takes to make these things. Compute wise, each 5 second video segment is 180 seconds on my laptop GPU, so the ten second video would take 6 minutes to generate if we just took the first video to pop out, and a 3 minute trailer would take an hour and forty minutes. But of course this is compute time, which can always just happen when we’re off doing something else, such as sleeping.

In terms of human effort I spent far more time writing this article than in making the video. Looking at my file timestamps, the edited images came out over the course of a single hour, one in which I largely was doing other things and letting the computer generate possibilities, then picking afterward. The videos were generated over the next couple hours, and I spent the most human effort at the end watching them and picking between them. So, three hours of gen on a laptop GPU, an unknown but much lower time of human effort. For ten seconds. Eh, well, it was cool and it was fun.

Currently, humans are better at animations than computers, so we can always improve animation by putting in more human time. Besides the obvious techniques of prompt iteration, picking the best variation, and prompt-based editing, we can be more direct. Given a video one likes with some flaws, one can improve it by manually editing intermediate frames to fix those flaws, then regenerating segments of the video using the edited frames as keyframes. Or, simply regenerating subsections one dislikes, perhaps with prompting changes, until one gets a better variant by one’s human judgement. So the upper time is unbounded, but we probably get to the “good enough” point within an hour or two and then face highly diminishing returns.

Thoughts on Automation

In theory, many of the steps could have been done by a vision-language model. Vision-language models are pretty good at object location. A vision-language model could locate the required comic panels, pick the coordinates of the corners, and crop out the necessary frames. It could figure out which panels were in a sequence which would have intermediate frames rather than cuts. It could, possibly, generate prompts to feed to a prompt-based editor to fill in the backgrounds and padding with somewhat consistent things, or we could do the oldschool animation technique of using a static background and panning it a bit, and simply isolate the foreground objects and paste them onto the background, if the location and camera angle isn’t changing much. All that could be done by a pipeline instead of a human, if the vision-language model could figure out which one of them to do.

Much of animation consists of fairly static images talking, possibly while moving a bit, which video generator models excel at producing. It’s fairly easy to detect when to animate this since there are dialog bubbles to show this, and computers are pretty good at reading the text in dialog bubbles. Detecting cases of people talking, using the vision-language model to tell the image editor to remove the dialog and fix up the background, then generating video and adding the dialog as audio is something that could be done fairly automatically, and for actual cartoons takes up fairly large amounts of the screen time. So much of this “filler” could happen automatically, even if we needed more human intervention for more action-type moments like what I’ve animated above.

Fundamentally, the biggest issue is that the computers aren’t that good at seeing what’s wrong and fixing it, or at least, what a human would consider to be wrong. While I’ve gotten acceptable levels of aesthetic judgement on still images working, I don’t think vision-language models are going to realize things like static flames being wrong if the video generation model doesn’t realize it. So, we would still need a human in the loop to detect such flaws and fix the final product. But of course, this is also true with human animation studios.

Conclusion

The current state of video models is sufficiently good for solo artists to make some pretty good-looking videos on their own laptops, but it’s still vastly more time-consuming than making a video via pointing a smartphone camera at yourself. Video models will likely find their current niche in making scenes that would impractical to film oneself in one’s own home, such as exotic backgrounds, non-human characters, superpowers, and animated cartoons.

Making a good video currently requires a lot of human intervention as well as processing time, but the automation feels pretty close. We may be approaching the point where I can take a comic book, feed it to a compute pipeline with no further human prompting, and wake up the next day with an animated video of it. But we’re not there yet.

Addendum (added a day later)

In the brief time since I wrote this, Black Forest Labs released Flux Klein, which gives prompt-based editing at subsecond speed. In theory this significantly reduces compute for keyframe editing, to the point where human time would be more than compute time. Also, in the time since I made the video, LTX-2 came out and blew up—an open-weights video model with baked-in audio. However, it doesn’t yet work too well for first-frame-last-frame, or multiple keyframes, at least for me, so WAN 2.2 remains the right choice for this application.